Zvonarka Bus Station

Brno, Czech Republic

Self-initiated in 2011, this redesign and restoration project saw the architects actively engage in preserving the existing Brutalist structure – a steel supporting frame and concrete roof – and its original architectural identity, reflecting CHYBIK + KRISTOF’s commitment to perpetuating architectural heritage. Stressing the station’s central role in the city and region’s sociocultural fabric, they address the urgency to rethink the use of a decaying transportation hub and public space. Placing transparency, and access, at the root of their design, they have transformed the bus terminal into a functional entity adapted to current social needs. Underlining the social awareness that consistently informs their projects, CHK affirm architects’ responsibility in acting as agents for positive social change.

Akin to the internationally renowned Hotel Praha and Transgas buildings in Prague, Brno’s Zvonarka Central Bus Terminal, built in 1988, has long been considered one of the notable remaining examples of the Czech Republic’s Brutalist architectural heritage. Dominating much of post-war architecture, Brutalism or “béton brut” – referring to the exposed concrete architecture that simultaneously celebrates progressiveness and experimentalism – has long polarized architects and scholars alike, among whom CHK. Like notable figures from Zaha Hadid to Kengo Kuma, they have consistently advocated for the preservation of Brutalist architectural heritage, citing its intriguing aesthetic and raw material qualities. With many such structures demolished or threatened in recent years – among which the now demolished Hotel Praha (2014) and Transgas (2019), the controversial Robin Hood Gardens (2017) in London and the Burroughs Wellcome Building (2021) in the United States, CHYBIK + KRISTOF affirm their engagement for their protection, placing the Brutalist Zvonarka Bus Terminal building as a local case-in-point of such circumstances.

“Demolitions are a global issue,” explains co-founding architect Michal Kristof. “Our role as architects is to engage in these conversations and demonstrate that we no longer operate from a blank page. We need to consider and also work from existing architecture – and gradually shift the conversation from creation to transformation.”

Designed in 1984 and built in 1988, the Zvonarka Central Bus Terminal has continuously acted as the region’s main bus station for intercity transport. In 1989, the building was privatized, with only the first phases of construction complete, and resuming its role as a bus station. Recognized as a Brutalist heritage site, its high maintenance costs led to little upkeep, driving to its gradual deterioration.

In 2011, CHK grew aware of the station’s decaying conditions. Eager to advance a positive alternative to a seemingly irrecoverable space, they reached out to its private owners with an elementary redesign proposal. Drawing wide public attention through social media, their initiative prompted a conversation between local private stakeholders and public authorities – and after a four- year-long collaborative exchange, the required funding was attained in 2015, notably through the project’s recognition as a European funds project. In 2021, ten years later, the architects now unveil the restored and redesigned transportation hub and public space – a preserved Brutalist heritage site and reconfigured functional space, attentive to both its history and to evolving social needs.

The Zvonarka Central Bus Terminal mirrors CHK’s profound social awareness in conceiving their projects. First identifying the ongoing social dynamics, they engage with diverse stakeholders – architects, public entities and private partners, local and external. Adopting a holistic sociocultural and technical approach, they ultimately bring forward a user-centered, conscious design – one that moves beyond the mere construction process. Stressing the station’s role as the point of entry into and departure from the city, they outline the significance of this transitional space, as transportation hubs increasingly come to act as windows onto cities. All-the-while conceiving a functional redesign receptive to users’ needs, the architects cultivate the station’s essence as the city’s social nerve, envisioning how to further integrate it in the surrounding urban fabric and invite new social dynamics within it.

“The role of the architect begins prior to the first sketches. Fully understanding the social dynamics at play in every project is at the heart of our practice,” states co-founder Ondrej Chybik. “With this in mind, we as architects assume a crucial role in both the inception and materialization of a project – we are here at the beginning, in the middle, and at the end. Instigating a dialogue; resolving the existing shortfalls – social, economic, cultural, and deeply political; bringing forward innovative and inclusive solutions – it is our responsibility to step out of our studios and onto the streets.”

True to these two engagements, CHK position themselves as both architects and citizens of this urban space. In doing so, they consider the inherent relationships, nuances and synergies between the existing and the envisioned, the public and the private, the function and the experience – all-the-while stressing the station’s primary role as a transportation hub, through which over 820 regional, national and international connections and 17,000 passengers transit each day.

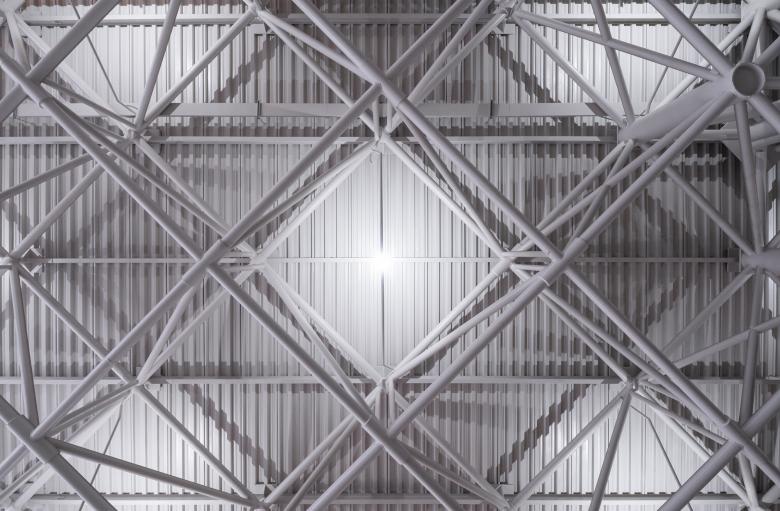

Transparency is at the root of their new design. Paying homage to its original architect Radúz Russ, they proudly expose the station’s characteristically raw Brutalist elements – a steel supporting frame and concrete roof – contrasting their angularity with an organic wave that mirrors the seamless flow of vehicles and passengers. They also turn to structural transparency, removing walls and favoring light as evocative of access, safety and comfort. Following the original square floorplan, they reconfigure the main hall as an open structure devoid of walls. A two-sided roof, the inner space houses the individual bus stops while the outer area serves as a parking space for buses. Eager to open up the terminal onto the city, the architects remove the temporary structures added in the 1990s and erect a second entry to the station at street level. Adding new light fixtures onto the main worn-down structure, which they repaint in white, they introduce a new information office, ticketing and waiting areas, platforms, and an orientation system accessible to the disabled. Through this design, CHK transform the building into a dynamic, functional and intrinsically social hub, channeling an unrestricted flow of locals and passengers alike.

Reflecting on this reconstruction and urban renewal project, Ondrej Chybik and Michal Kristof state: “While our familiarity with the city of Brno proved to be a real asset, our engagement for this project resonates with architects internationally. Beyond a functional concern, the architects’ role is rooted in understanding, deconstructing and responding to the shortcomings that often form our social structures – that is, our role is intrinsically social, based on ‘people.’ Ultimately, by revisiting the past, engaging with the present and projecting to the future, architects can, and must, be catalysts for change.”

In addition to the redesign of the Zvonarka Central Bus Terminal and of its surrounding areas to unfold gradually in the coming years, CHK have initiated several redevelopment projects in Brno. Among these, the Mendel Square and Mendel Greenhouse projects, to be completed in 2022 in homage to the notorious scientist and father of modern genetics on the 200th anniversary of his birth, will in turn revisit the existing space, a distinct heritage site, as an open transportation hub – rooted in Brno’s longstanding history and responsive to its evolving social dynamics.

- Location

- Brno, Czech Republic

- Year

- 2020