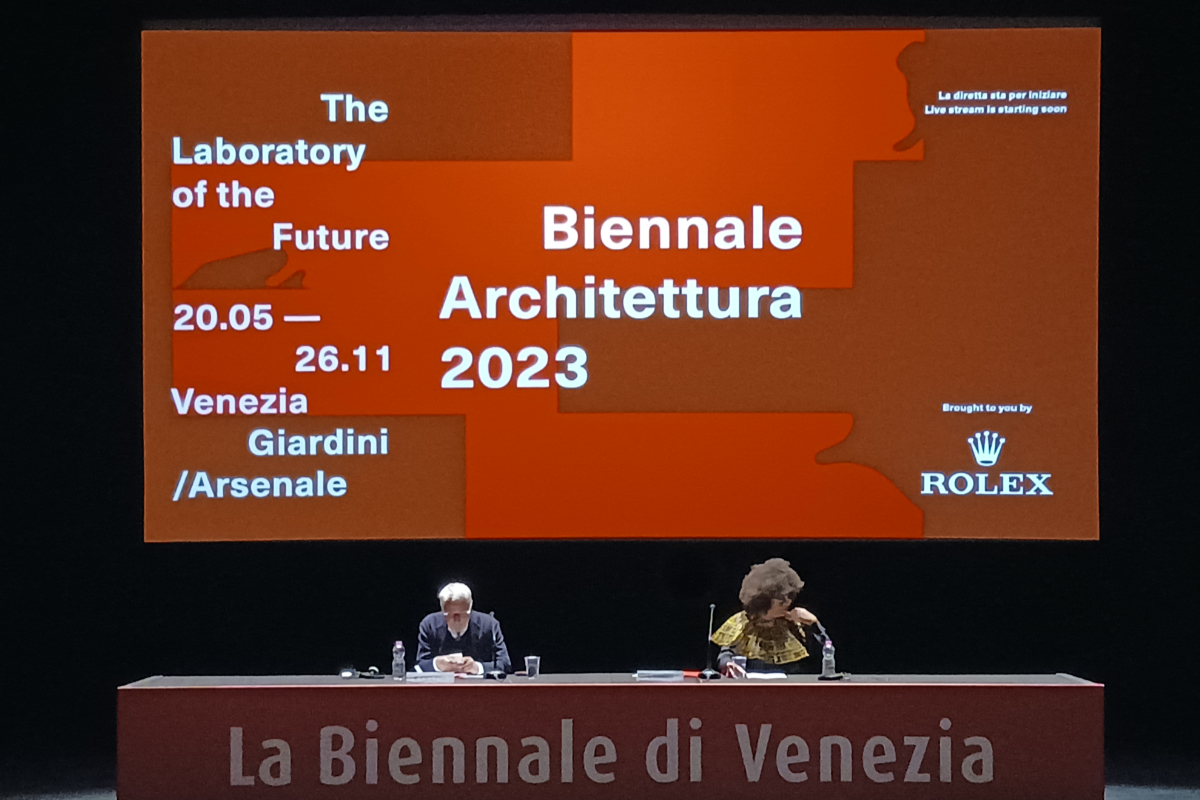

Lesley Lokko with Biennale president Roberto Cicutto (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

Lesley Lokko Addresses 'an Old and Familiar Tale'

John Hill

Lesley Lokko with Biennale president Roberto Cicutto (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

Lokko began the brief press conference by acknowledging the “three sets of people to whom everything is owed: participants, teams, and donors.” The research team and curatorial assistants that comprise the second are made up primarily of people from the African Futures Institute, which she established in Accra, Ghana, in 2021 and was just four months old when she was selected for the Biennale in December of that year. At the time the institute “consisted of me, a cleaner, and a driver” but has grown to “now three teams of 18 people around the world.” Their efforts led to the unearthing of the young talent whose work "threads through the exhibition, in what has already become a collective outpouring of pride and joy.”

After thanking sponsors including Rolex and Bloomberg Philanthropies for placing “their trust — and their money — in an idea, nothing more,” Lokko addressed the recent controversy that has garnered the most attention in the days leading up to the Biennale: the Italian government's denial of visas to three members of her team under the guise of “trying to bring ‘non-essential young men’ into Europe.” “For almost the first time in my life,” she told the room of journalists, “words failed me.” Specifically, the rejection letter from the Italian Embassy in Accra read: “There are reasonable doubts as to your intention to leave the territory of the member state before the expiring of your visa.” Yet, Lokko said, there was no clarification as to what those “doubts were, reasonable or otherwise.”

The Italian Ambassador to Ghana wrote in a press release to journalists wishing clarification on the issue: “Our embassy is deeply committed to promoting collaboration with Ghana in all sectors, including in the cultural field. And we spare no efforts to facilitate the participation of Ghanian artists in art exhibitions or events scheduled in Italy where we are at the forefront of policies to promote African cultural heritage, both tangible and intangible.” After reading this statement, Lokko stated bluntly: “This is not the forefront of policy. This is its ugly rear.” Although there is a saying that any attention is good attention, Lokko does not want the “headline story” of the denied visas to be “the defining story of this exhibition”; after all, “this is not a new story. It's an old and familiar tale.”

Lokko recounted a story of being depressed and unable to work following the election of George W. Bush to a second presidential term in 2004; a friend told her that “times of dread” are precisely when artists must go to work: “There is no time for despair, no place for self pity, no need for silence, no room for fear.” Similarly, Lokko, her team, and the dozens of participants in The Laboratory for the Future “understand that this is precisely the time to go to work.” She explained that “over the coming months — thoughtfully, intelligently, carefully — participants will use the platform of this exhibition to work together to address the complex questions that have been raised.”

Lokko then touched briefly on the guiding framework of the exhibition — decolonization and decarbonization — in terms of the physical makeup of the exhibits (“screens, films, projections, and drawings in place of models and artifacts, wherever possible”) and the aims of their content: “The intention is not to replace, but to augment; to expand, not to contract; to add, not subtract.” Finally, just a short twelve minutes after beginning her remarks, Lokko wrapped up her remarks by reading a letter she wrote following her appointment as curator:

“Dear Team – There are many ways to start a creative project. Sometimes it begins with an idea, a kernel of truth that the author or curator hatches in the wee hours of the morning when the rest of the world is asleep and the mind wanders fluidly, easily. The idea grows, acquiring depth and weight, until it is formed enough to be shared. But other times, an idea or concept appears fully formed, usually born after the conversations that proceeded it. Occasionally, however, it is not ignited by a single spark, but is rather the crystallization of many ideas whose prominence can be traced back over the years, sometimes decades. This letter is addressed to the team of disparate and dispersed people who make up the African Futures Institute and the Biennale project. It is akin to manifesto, but written in a different key. Think of it as a love letter, a passionate description of the task that lies ahead. It is both personal and public. It is for you, but it is also about and of you. It was written in one place, in one go, but I have been writing this all my life.”

I have not heard such loud and sustained applause in a press conference as that which followed her words.