Photo: Flavia Rossi

5 Lessons from Lesley Lokko's 'The Laboratory of the Future'

John Hill

Photo: Flavia Rossi

Ever since Scottish-Ghanaian architect, author, and educator Lesley Lokko was selected to curate the 18th International Architecture Exhibition, it was clear it would be different from every previous Venice Architecture Biennale. Just a few months prior to her appointment in late 2021, Lokko had founded the African Futures Institute in Accra, Ghana, and her exhibition would be the first to focus on Africa, pulling more than half of the exhibition's 89 participants from the continent and the African diaspora. Further reflecting Africa's demographics, the average age of the participants would end up being just 43, with roughly half of the practitioners in the exhibition hailing from firms with fewer than six architects. These and other statistics “reflect a seismic change in the culture of architectural production at large,” Lokko writes in the introduction to the 18th International Architecture Exhibition, The Laboratory of the Future, “and an even greater shift in participation in international exhibitions. The balance has shifted. Things fall apart. The center can no longer hold.”

The majority of the exhibition consists of four parts in two venues. The Laboratory of the Future begins in the Giardini with Force Majeure and its presentation of sixteen practices of African and Diasporic architectural production in the Central Pavilion. The exhibition continues in the Arsenale with the large Dangerous Liaisons section, in which “practitioners working at the productive edge between architecture and its myriad ‘others,’” Lokko writes in the exhibition's catalog, “charting new territories of professional and conceptual relevance and urgency.” Guests from the Future, the work of young African and Diasporan practitioners, threads through both venues, while the Curator's Special Projects — in the categories of Mnemonic; Food, Agriculture and Climate Change; and Geography and Gender — sit at the far end of the exhibition in the Arsenale. Additionally, the exhibition has a large-scale installation at Forte Marghera in Mestre and Carnival, a six-month-long cycle of events, lectures, panel discussions, films, and performances leading up to its closure in November.

Loom installation in Central Pavilion (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

Walking through The Laboratory of the Future during the Biennale's two-day vernissage ahead of its opening on May 20 was exhilarating and intellectually stimulating but also, at times, confusing and frustrating. Visitors used to a narrow view of architectural exhibitions as venues for displaying the work of architects — buildings and projects in drawings, models, and the like — might be disappointed. But those open to expressions of ideas and critiques using a variety of means, from painting and sculpture to film and installation, should find much to like — and should leave the exhibition feeling refreshed and optimistic about the future. My repeated visits over those two days yielded many lessons, a handful of them described below.

From indigenous learning to dealing with scarcity, Africa's lessons for the future are many

Exhibit on Demas Nwoko in the Book Pavilion (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

When the gates opened on the first day of the vernissage, I was in the minority: Instead of making a beeline for the Central Pavilion (top photo), its new facade beckoning architects like proverbial moths to flames, I veered right, walking into the Book Pavilion to see the small exhibit devoted to Nigerian architect and polymath Demas Nwoko, recipient of the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement. If the Africa of today is, in the context of this Biennale, a laboratory of the future, what came before? What architecture on the continent is being commended with this high honor? Texts accompanying the display of Nwoko's books and projects describe him early in his career as “a proponent of a forward-thinking artistic philosophy — one that rejected the European-centric frameworks of artistic expression to instead redefine and embrace an indigenous Nigerian style.” The approach resulted in such buildings as the Dominican Institute and Chapel (1975) in Ibadan and ongoing projects like the New Culture Studios, his own studio and a place of experimentation, also in Ibadan.

ACE/AAP by Olalekan Jeyifous (Photo: Flavia Rossi)

A similar embrace of indigenous learning over outsider influences is found in Olalekan Jeyifous's Silver Lion-winning contribution to the exhibition occupying the whole mezzanine gallery in the Central Pavilion. ACE/AAP is a “retrofuturist African eco-fiction” that is set in an alternative decolonial timeline when resource exploitation and extraction have been dismantled and given way to environmental efforts that consolidate into the African Conservation Effort (ACE). The group applies indigenous knowledge to projects using renewable energies and green technologies, the flagship being the All-Africa Protoport (AAP), a sustainable means of traveling rapidly via air, land, and sea. The exhibit is set up as a lounge at one node in the AAP network that, in Jeyifous's infectiously optimistic timeline, has been exported from Africa to other parts of the globe. More than any contribution to the main exhibition, ACE/AAP truly imagines Africa as the laboratory of the future, creating a space that is familiar, like something from the mid-century heyday of airports, but has enormous ambition: using indigenous knowledge to create better futures in and beyond Africa.

Time and Chance by Studio of Serge Attukwei Clottey (Photo: Flavia Rossi)

Many of the contributions to The Laboratory of the Future are not as straightforward as ACE/AAP. Visitors must have patience reading wall texts, watching films, and metaphorically scratching beneath the surface to find meaning and relevance in the exhibits. Two large pieces by the Studio of Serge Attukwei Clottey are on display, both taking the name Time and Chance: one hung on a wall in the long Corderie of the Arsenale and a more substantial site-specific piece suspended from the supports of the Gaggiandre (photo above). The yellow, fabric-like installations are made from discarded plastic containers that lend the Ghanian artists's series of works the name “Afrogallonism.” Beautiful from afar, when seen up close the components of the artworks — small squares stitched together in an un-self-conscious manner — clearly exhibit the objects from which they were made, with stickers, corrugations, and even bits of mold part of the expression. Tosin Oshinowo's essay in the exhibition catalog, though not mentioning Clottey, resonates with his work: “As the rest of the world faces similar scarcity challenges [to Africa] due to our urgent climate crisis, the continent's resilience is a case for an alternative approach.”

Decolonization and decarbonization are linked

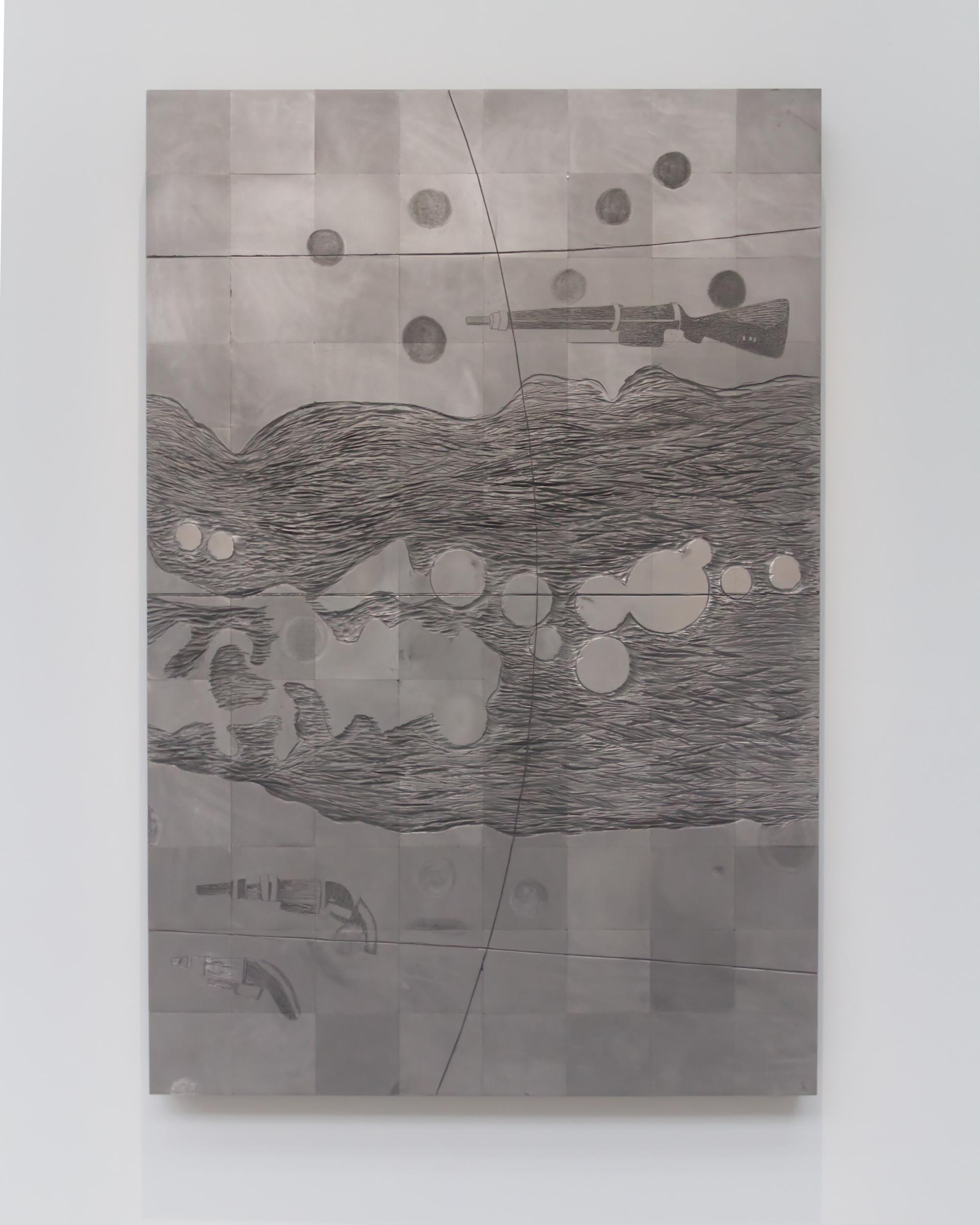

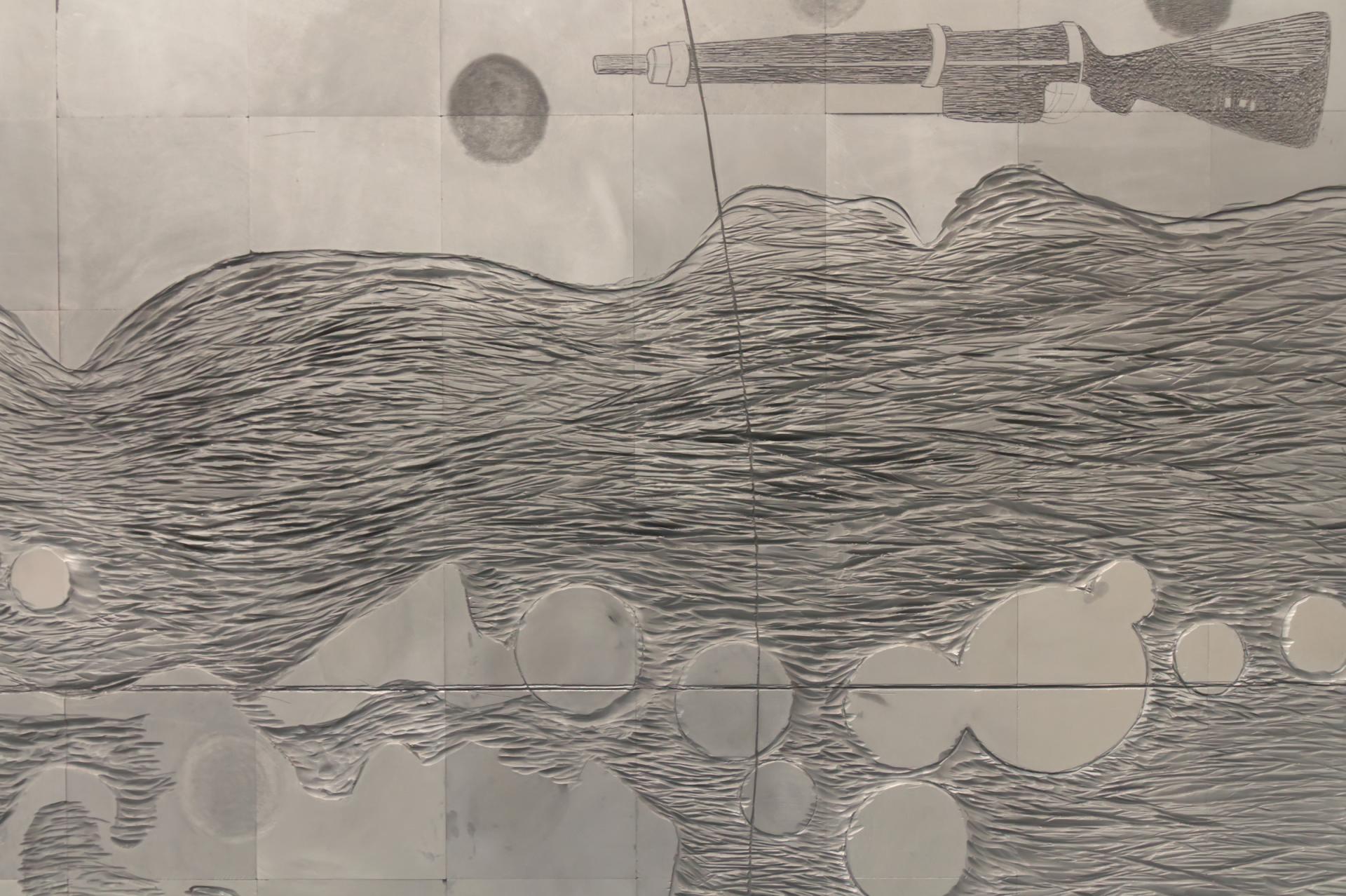

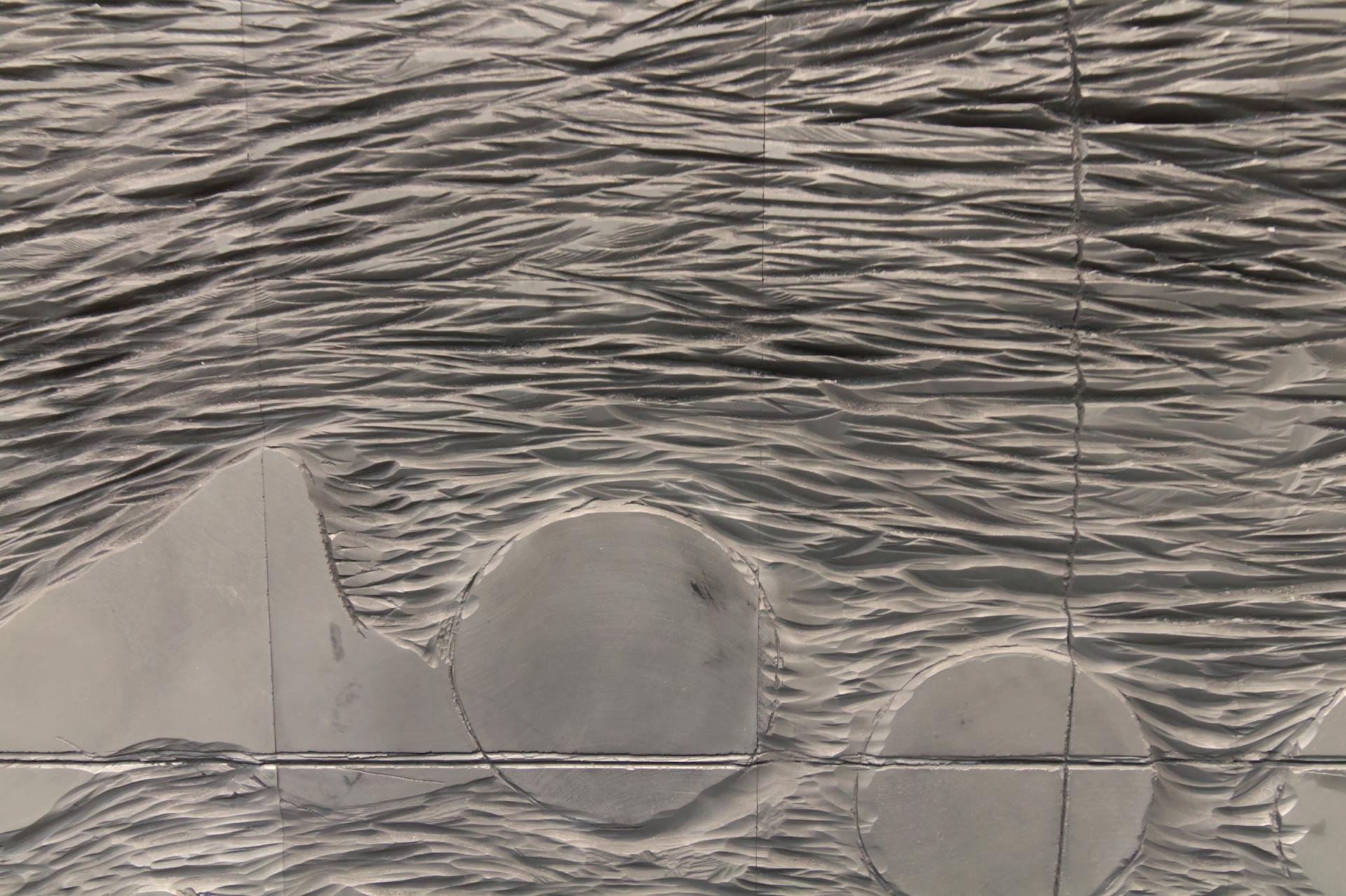

The Uhuru Catalogs by Thandi Loewenson (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

Following Lesley Lokko's brief comments during the vernissage press conference, a journalist asked the curator about the link between decolonization and decarbonization, the twin themes of The Laboratory of the Future that she gave as “guiding principles” for the practitioners contributing to the exhibition. “The black body was Europe’s first unit of energy,” she replied. “When we talk about decarbonization, we are not only looking at it through a scientific, quantitative lens. It is intimately entwined with decolonization.”

The Uhuru Catalogs by Thandi Loewenson (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

Architect and curator Luca Molinari's essay in the exhibition catalog, “To Work on Words and Actions,” echoes Lokko's statement, saying that the “clear relationship” between decolonization and decarbonization “cuts across all forms of social, economic, and environmental inequality under which most of the world's population lives.” To avert climate catastrophe, the world cannot continue to see places, in the still entrenched colonial manner, “as if they were a perennial and inextinguishable resource.”

The Uhuru Catalogs by Thandi Loewenson (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

Thandi Loewenson was recognized by the international jury for her contribution to the main exhibition, The Uhuru Catalogs, which, in their citation, “materializes spatial histories of land struggles, extraction, and liberation through the medium of graphite.” It articulates the intertwining of decolonization and decarbonization more effectively than any piece in the Biennale. Medium is the message, as the drawings are composed on blocks of industrial graphite, the material typically used in the production of lithium-ion batteries and therefore in short supply due to increased global demand. “Here, graphite is put to use as a conduit, a charged medium,” Loewenson writes, “that aims to energize a consciousness of the conjoined terrains of earth and air in movements for climate justice and equitable futures for all.”

The Uhuru Catalogs by Thandi Loewenson (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

Architecture is a political act

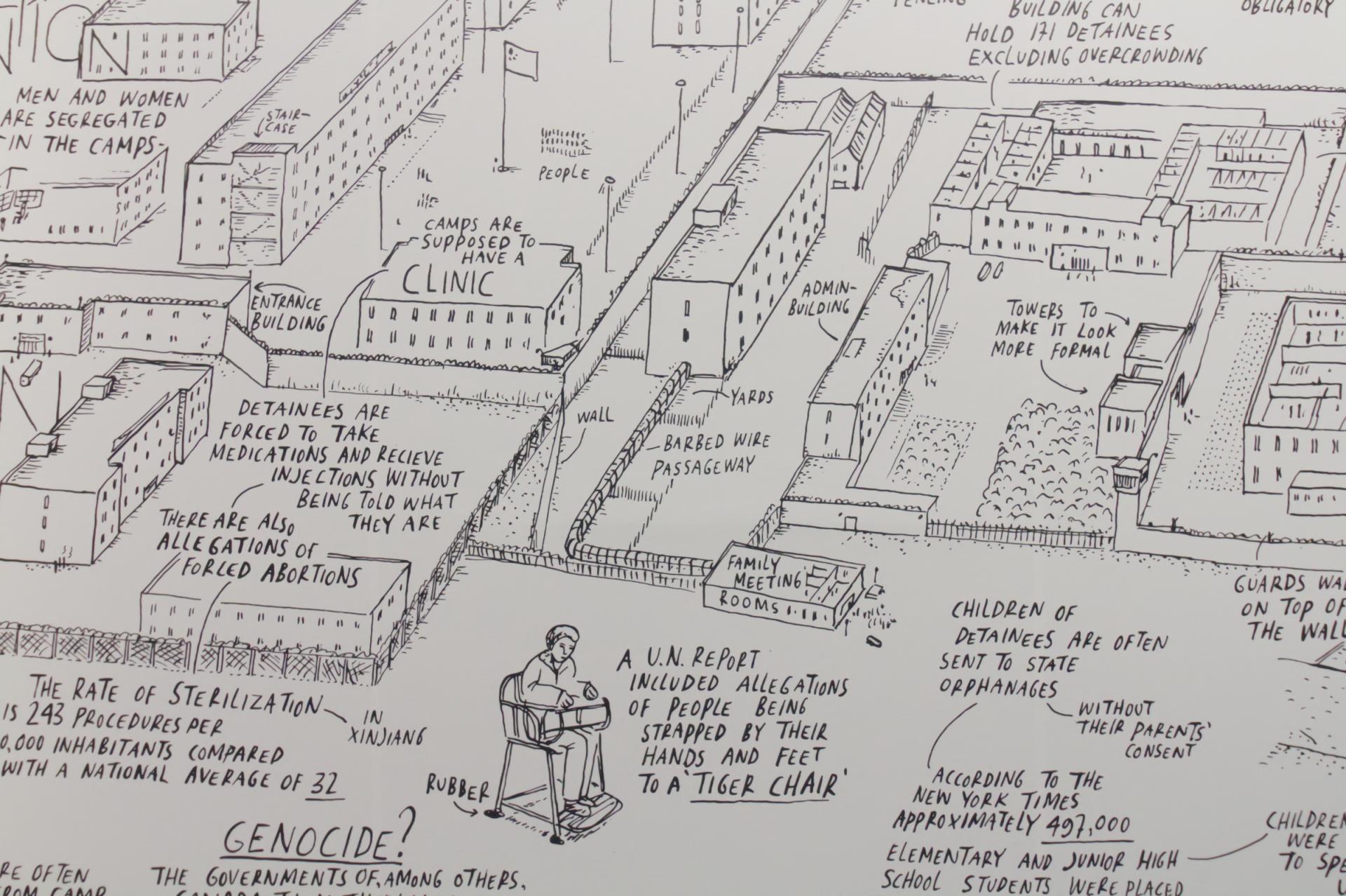

Investigating Xinjiang's Network of Detention Camps by Killing Architects (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

Architecture is a practical art and therefore is in many ways political. Architects must navigate bureaucratic requirements when designing buildings and getting them approved. They need to be cognizant of a variety of social demographics in the use and occupation of buildings and landscapes, especially public ones. They need to consider the environmental impact of their designs, meeting baselines requirements set up in local jurisdictions but also exceeding them, when possible. And, as projects like NEOM bring to the fore, architects often work for clients that could be described as political landmines. But architecture is also a means of being political in more confrontational ways: addressing environmental, humanitarian, and other sensitive topics through an architectural lens and with architectural tools.

A few days after the Venice Architecture Biennale opened to the public on May 20, news broke that the “Chinese Embassy [had] dropped out of the influential international cultural exhibition due to a 30-minute documentary about the Xinjiang detention camps, blasting it as ‘fake news.’” The documentary, Investigating Xinjiang's Network of Detention Camps by Killing Architects, uses “visual and spatial methods such as satellite imagery, 3D modeling, and analyses of the Chinese prison building regulations” to conclude, from a distance, “that each site was a detention camp,” something the Chinese government refutes. The film takes place inside a room within the Arsenale, while a wall drawing on the outside (photo above) mixes architectural isometrics with descriptive notes and journalistic accounts.

The Nebelivka Hypothesis by David Wingrow and Eyal Weizman with Forensic Architecture and The Nebelivka Project (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

Farther along in the Arsenale is The Nebelivka Hypothesis, which pairs archaeologist David Wingrow with Eyal Weizman of Forensic Architecture, the research agency known for using architecture as a tool of forensics, particularly for investigating human rights violations. Presented as a video projected onto a rectangular recess in the floor, The Nebelivka Hypothesis explores an underground area in central Ukraine that is home to a 6,000-year-old settlement that may provide evidence of a past civilization actually improving the soil it subsisted upon: “a system of urban life that enhances the vitality of its own environment.” The relevance of this ancient civilization to today's environmental crises is abundantly clear.

Xholobeni Yards: Titanium and the Planetary Making Of Shininess/Dustiness by Andrés Jaque/Office for Political Innovation (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

Further along the Corderie is Xholobeni Yards: Titanium and the Planetary Making Of Shininess/Dustiness, an immersive multimedia presentation by Andrés Jaque/Office for Political Innovation that focuses on the “transnational extractivism” of New York City's Hudson Yards. The title refers to the Xolobeni mine in South Africa, whose ilmenite deposits were used to create the reflective titanium cladding on skyscrapers such as those at Hudson Yards (organized community opposition means the mine is currently closed). Other minerals mined from the African continent — “chromite extracted from the earth of the Great Dyke of Zimbabwe” and “cobalt extracted from the Nyungu mines of Zambia” are two articulated in the catalog — are needed to give corporate developments like Hudson Yards its shine. But the titanium extracted from the ilmenite leaves in its place a dust that easily blows in the wind, an effect expressed by the red light bathing the installation at times.

Everybody loves immersive installations

Native(s) Lifeways by Hood Design Studio (Photo: Flavia Rossi)

Okay, I'll admit this lesson's statement is hardly a universal truth, but if any type of exhibition should exploit the potential of immersing visitors in singular installations, it's architectural ones. After all, architectural education and practice are geared to, in large part, the creation of space: the rooms and other environments that impact the lives of buildings' users and inhabitants. There is no shortage of contributions to The Laboratory of the Future that are in this vein, from the colorful porticoes at the entrances to the two venues, to Loom (photo at top) and other room-sized installations carried out by the curatorial team, to single participants taking over rooms in the Central Pavilion or large bays in the Arsenale.

An unexpected intervention is found in the Central Pavilion's outdoor sculpture garden that was redesigned by Carlo Scarpa in 1952 with paving, two small pools, and a curved canopy supported on three columns. Landscape architect Walter Hood softened the space with a layer of plantings, curious columns made from splayed timber pieces, wooden walkways, and graphic panels appearing to depict gondoliers from past eras. Native(s) Lifeways is an expression of Hood Design Studio's project for Phillips, a small Black community near Charleston, South Carolina; it is accompanied by an in-depth presentation of the project within the Central Pavilion. The columns, the most overly interesting part of the design, were inspired by the large rice-toting baskets that men used for harvesting on the former plantation that Phillips occupies.

Counteract by Kéré Architecture (Photo: Flavia Rossi)

Much like Lesley Lokko is the first person of African descent to curate the Venice Architecture Biennale, architect Diébédo Francis Kéré is the first African and Black winner of the Pritzker Architecture Prize. With such credentials, it's no surprise the 2022 laureate's contribution cannot be contained within one gallery within the Central Pavilion. Counteract's earthen walls snake from a large gallery it shares with Thandi Loewenson's graphite etchings to a small gallery, where its curved walls form a circular seating area inside and are capped by a dramatic roof on the outside. It's a modest yet beautiful installation that encourages visitors to get close to it via small videos housed within round portals in the walls. The look, feel, and even smell of the walls are rich, presented as a “‘counteract’ to the chase for modern architecture,” per the catalog, and a celebration of “West African architectural prowess of the past.”

Kwaeε by Adjaye Associates (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

Easily the largest contribution to the International Architecture Exhibition is the wedge-shaped timber pavilion designed by Adjaye Associates and placed as a freestanding object at the far end of the Arsenale. Though large, Kwaeε is actually just one of four contributions by David Adjaye, who has a room with films at the entrance to the Central Pavilion, a gallery with models of a few architectural projects, and his firm's just unveiled proposal for the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art in India. Kwaeε is “envisioned as a space for both reflection and active programming,” per the catalog, designed as a cave-like space punctuated by two oculi. Made entirely from darkened wood, the structure was made to host lectures and panel discussions but also as “a space for archival auditory experiences.”

Environmental sustainability requirements mean a lot of films*

Looking toward Rhael “LionHeart” Cape's Those With Walls for Windows from the Freespace-esque square near the start of the Arsenale (Photo: Flavia Rossi)

Speaking with architect Ricardo Flores amidst the impressive installation that almost literally transplants the studio of Flores & Prats from Barcelona to the Arsenale, he explained to me that Lesley Lokko asked them not to create anything new for the Biennale — do not create any waste. I knew a little bit about La Biennale di Venezia's recently implemented commitment to environmental sustainability, but this conversation was the first time I considered it from the perspective of a participant in the exhibition, rather than as an attendee (my trip to Venice for the vernissage required me to indicate how I was getting there and where I was coming from, in effect determining my carbon footprint as an attendee). In terms of materials, the Biennale recommends minimizing the use of raw materials, using renewable or recycled materials, and using materials that “are conceived to extend their useful life, and can therefore be reused as they are in other Biennale events or elsewhere.” Hearing Flores explain the impact of the commitment on their installation made it click for me: So that's why there are so many films in the exhibtion!

Welcome in Nomadland by Le laboratoire d'architecture (Photo: Flavia Rossi)

Before reaching the Emotional Heritage installation by Flores & Prats, situated just one-quarter the way through the Arsenale's Corderie building, I had encountered about a handful of films from the sixteen contributions in the Central Pavilion and a few films in the Arsenale; one of the latter, Aequare: The Future that Never Was by Twenty Nine Studio and Sammy Baloji, would receive a special mention from the international jury a couple of days later. The balance of the exhibition in the Corderie and Artigliere has no fewer than twenty contributions that are wholly or in part comprised of film or video projections. In total then, about a third of the 89 contributions to The Laboratory of the Future include films, following from Lokko's remarks during the press conference that the participants use “screens, films, projections, and drawings in place of models and artifacts, wherever possible.”

Ente di Decolonizzazione — Borgo Rizza by DAAR – Alessandro Petti and Sandi Hilal (Photo: Flavia Rossi)

What does it mean to have a Biennale with so many films? Visitors have numerous chances to sit down, take a break from the long walk through the exhibition, and watch what are in the majority short films. (That said, the distribution of the filmic contributions is not even; it is clustered toward the latter half of the long Corderie and in the perpendicular Artigliere.) But these contributions ask a lot from visitors, who can walk by drawings or models at their own pace and own level of engagement, but might be more inclined to engage with the films aping for their attention via sound as well as image. Yet it's not hard to imagine that many of the films could be available online, on YouTube or Vimeo, if not now then in the future, to be watched at will after the Biennale. Therefore the best filmic pieces are integrated with the setting and/or the content, as in the examples shown here. Among them, DAAR's Golden Lion-winning Ente di Decolonizzazione - Borgo Rizza stands out: The film explains the shape of the seating that visitors engage with and expands the exhibit temporally and spatially well outside the confines of the Arsenale.

Embodiments: Port of Shir — Final Act by Gugulethu Sibonelelo Mthembu (Photo: Flavia Rossi)

*And a lot of QR codes

Spanish Pavilion: FOODSCAPES (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

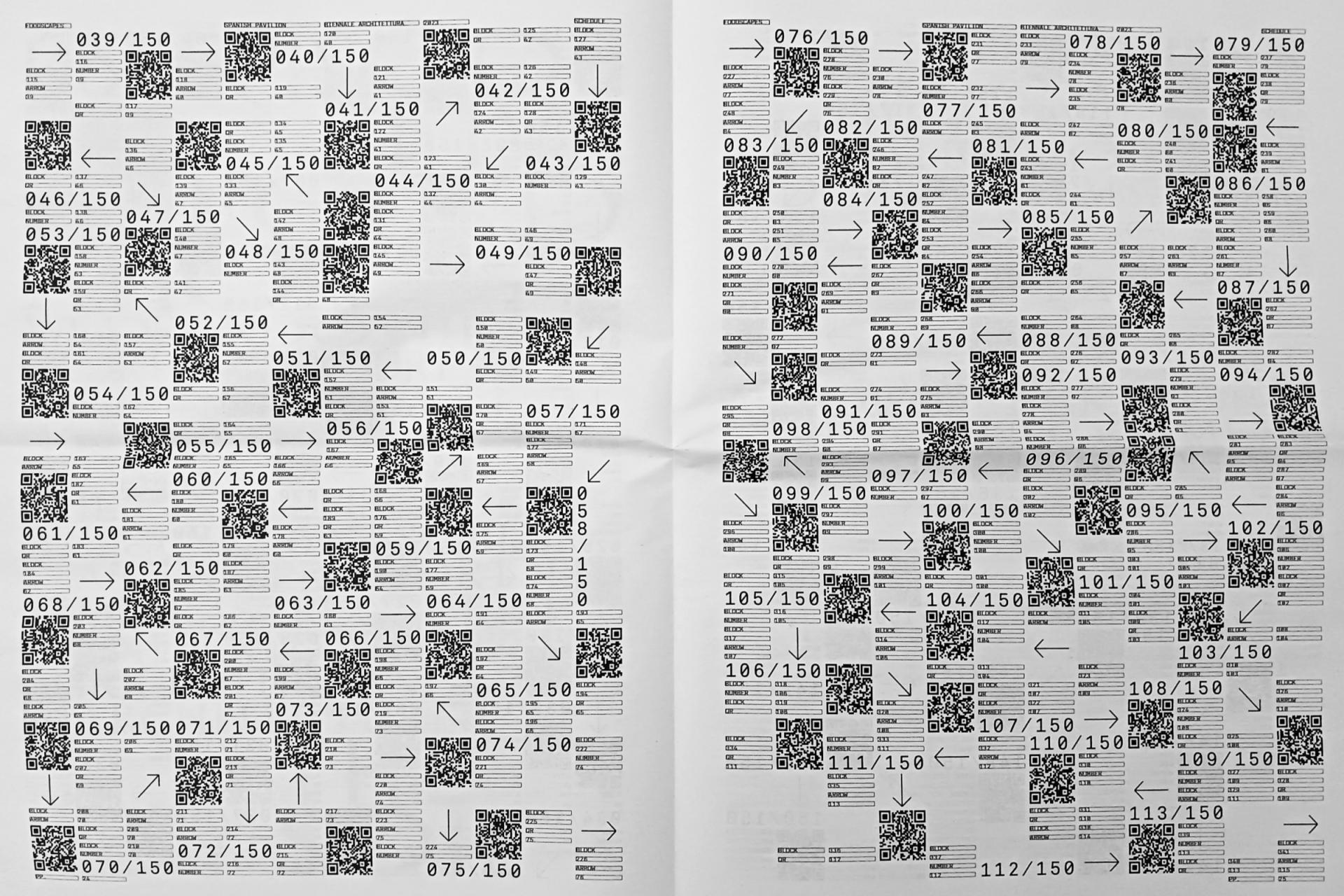

As an addendum to the lesson learned about films, it should be noted that many of the national pavilions rely heavily on QR codes, pointing visitors to websites with architectural projects and other things only partly displayed in the pavilions. While the national pavilions do not need to follow the theme of the main exhibition, they do need to abide by the Biennale's environmental sustainability rules now in place. Nowhere is a shift from artifacts to films and QR codes more apparent than in the Spanish Pavilion, FOODSCAPES, which consists of “five short films; an archive in the form of a recipe book; and a public program of conversations, debates, events and collective research.” The films are found in small darkened galleries off the central space, whose walls are covered with large photographs accompanied by QR codes, many of them out of reach. A newsprint allows visitors to scan the codes — all 150 of them — that lead to single-page PDFs with images, titles, and credits on the various “foodscapes.”

Center spread from FOODSCAPES newsprint (Photo: John Hill/World-Architects)

The questions and implications of so many QR codes are numerous: Will architectural exhibitions shift from presentations on gallery walls to digital content on our phones? If so, what will become of the galleries? Will immersive and more art-centric installations become the norm, over traditional architectural representations? (I'd be happy with that.) Perhaps these and other relevant questions will be addressed in two years, when the next Biennale takes place in Venice. Until then, The Laboratory of the Future is on display until November 26, 2023.